Decision Trees¶

After linear regression, decision trees are probably the second most commonly known model used for regression. Decision trees are completely different from linear regression, in that they are not represented by an equation. They are still functions (mathematically-speaking), because a function is just a rule which assigns an output given an input. But the function looks completely different from what you’re used to.

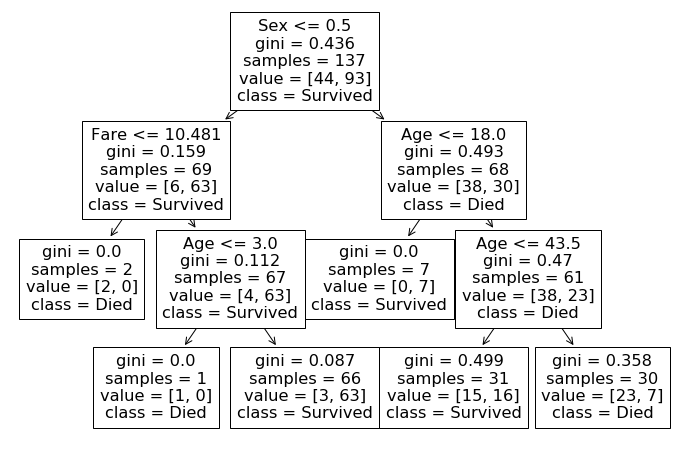

Below is an example of a decision tree being used to determine whether or not a passenger on the Titanic would survive:

We refer to each “question” in the tree (e.g. “Is age > 9.5?”) as a “leaf” or “node”. A question you may be wondering is, how do we know what questions we should be asking at each leaf? Also, what should the cutoff be for each question? Why are we asking about age being greater than 9.5 instead of 10, 11, or something else altogether? The answer is, decision trees automatically learn what questions to ask in order to generate the best possible predictions. Let’s jump in and start exploring.

Imports¶

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.preprocessing import LabelEncoder

Loading data¶

For this project we’ll be working with the finishing times for male runners in the LA Marathon. We’ll be training on model on 2016, and testing it on 2017. I scraped the data from the official results site.

df = pd.read_csv('data/2016_la_marathon.csv')

df.head()

| div_place | name | bib | age | place | gender_place | 5k_split | 10k_split | 15k_split | 20k_split | 25k_split | 30k_split | 35k_split | 40k_split | clock_time | net_time | hometown | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | SAUL VISCARRA | 40402 | 15 | 382 | 352 | 22:28 | 44:00 | 1:04:56 | 1:26:24 | 1:48:24 | 2:11:32 | 2:37:42 | 3:01:56 | 3:22:41 | 3:11:51 | NaN |

| 1 | 2 | FERNANDO GOMEZ | 40504 | 15 | 560 | 504 | 22:37 | 45:17 | 1:07:50 | 1:31:42 | 1:55:46 | 2:19:58 | 2:44:35 | 3:09:32 | 3:23:09 | 3:18:54 | NaN |

| 2 | 3 | MARCOS GONZALEZ | 40882 | 15 | 1042 | 881 | 24:08 | 47:44 | 1:10:34 | 1:34:10 | 1:58:40 | 2:23:37 | 2:54:01 | 3:23:20 | 3:43:35 | 3:31:59 | NaN |

| 3 | 4 | LUIS MORALES | 42286 | 13 | 1294 | 1076 | 22:50 | 46:21 | 1:11:07 | 1:34:42 | 1:58:49 | 2:24:17 | 2:54:27 | 3:26:22 | 3:41:55 | 3:37:24 | NaN |

| 4 | 5 | PETER CASTANO | 20099 | 15 | 1413 | 1166 | 26:13 | 53:12 | 1:19:36 | 1:45:47 | 2:11:53 | 2:38:18 | 3:03:38 | 3:29:46 | 3:45:48 | 3:39:31 | NaN |

Data preparation¶

Let’s start with our usual check of NaN/None values.

for col in df.columns:

missing_value_count = df[col].isna().sum()

print(f'{col}: {missing_value_count} missing')

div_place: 0 missing

name: 0 missing

bib: 0 missing

age: 0 missing

place: 0 missing

gender_place: 0 missing

5k_split: 821 missing

10k_split: 158 missing

15k_split: 101 missing

20k_split: 91 missing

25k_split: 73 missing

30k_split: 140 missing

35k_split: 95 missing

40k_split: 161 missing

clock_time: 0 missing

net_time: 0 missing

hometown: 11499 missing

It looks like a number of them are missing. This could be from people dropping out of the race, never showing up, etc. Since we’re trying to predict finishing time, let’s drop any rows which having a missing split.

split_columns = ['5k_split', '10k_split', '15k_split', '20k_split', '25k_split', '30k_split', '35k_split', '40k_split']

df = df.dropna(how='any', subset=split_columns)

We want to predict the runners placing based on their how fast they run, along with potentially some other information. Currently, their splits (times) at each 5 kilometers is written in the form hours:minutes:seconds. That’s not really what we want, we need numbers to work with. So we’ll start by converting those values to minutes. To do so we’ll use the Pandas .apply() function, which takes in a function, and applies it to each row individually.

Let’s write our function to look for the ‘:’ character, and then split at it. Note that depending on how fast/slow the runner was, there could be more than one colon in their time (for hours:minutes:seconds versus just minutes:seconds). So we’ll need to check the length of our list and process each part individually. To convert seconds into minutes we’ll divide by 60, and to convert hours into minutes we’ll multiply by 60. Finally, since we’re starting with a string, when we split it, we will again receive strings. Let’s do a simple test case first to make sure we have the idea.

speed_split = '23:45'.split(':')

print(f'The value {speed_split[0]} is a {type(speed_split[0])}')

print(f'The value {speed_split[1]} is a {type(speed_split[1])}')

The value 23 is a <class 'str'>

The value 45 is a <class 'str'>

This works, but if we’re going to do math, we need integers, not strings. So we’ll convert each to an integer as well.

speed_split = '23:45'.split(':')

print(f'The value {int(speed_split[0])} is a {type(int(speed_split[0]))}')

print(f'The value {int(speed_split[1])} is a {type(int(speed_split[1]))}')

The value 23 is a <class 'int'>

The value 45 is a <class 'int'>

Let’s now write our function to take in an arbitrary speed (written as a string), split it up, convert it to minutes, and return it.

def split_to_minutes(speed):

speed_split = speed.split(':')

# If there's only one colon, so minutes:seconds

if len(speed_split) == 2:

minutes = int(speed_split[0]) + int(speed_split[1])/60

# If there's two colon, so hours:minutes:seconds

if len(speed_split) == 3:

minutes = 60*int(speed_split[0]) + int(speed_split[1]) + int(speed_split[2])/60

return minutes

Let’s test it.

split_to_minutes('10:35')

10.583333333333334

With that, we can now apply our function to our dataframe. It’s good practice to not overwrite a column in a dataframe, because maybe you’ll need it later. So we’ll create a new column for each 5 kilometers, titled 5k_split_min, 10k_split_min, etc., as well as any other columns with times in them. We could go through and do this one at a time, but by using a for loop we can save ourselves time.

# An error is coming...

time_columns = ['5k_split', '10k_split', '15k_split', '20k_split', '25k_split', '30k_split', '35k_split', '40k_split', 'clock_time', 'net_time']

for col in time_columns:

df[f'{col}_min'] = df[col].apply(split_to_minutes)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ValueError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-11-23ed3fc323d1> in <module>

3

4 for col in time_columns:

----> 5 df[f'{col}_min'] = df[col].apply(split_to_minutes)

~/anaconda3/envs/math_3439/lib/python3.8/site-packages/pandas/core/series.py in apply(self, func, convert_dtype, args, **kwds)

3846 else:

3847 values = self.astype(object).values

-> 3848 mapped = lib.map_infer(values, f, convert=convert_dtype)

3849

3850 if len(mapped) and isinstance(mapped[0], Series):

pandas/_libs/lib.pyx in pandas._libs.lib.map_infer()

<ipython-input-9-0f784b837919> in split_to_minutes(speed)

3 # If there's only one colon, so minutes:seconds

4 if len(speed_split) == 2:

----> 5 minutes = int(speed_split[0]) + int(speed_split[1])/60

6 # If there's two colon, so hours:minutes:seconds

7 if len(speed_split) == 3:

ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: '0-33'

Oh no! Reading the error, it looks like someone has a time of ‘0-33’ which is causing issues when we try to convert it to an integer. So perhaps we should modify our function to first check for a valid value, and if it’s not valid, to just fill in a None. Then we can drop rows with None afterward. To do so, we’ll use the Python pattern try…except…. What this does is to try and do what you ask, but if an error occurs, rather than just crashing and throwing the error, it enters the except block. You can then make something else happen in there, like filling in a None.

def split_to_minutes(speed):

speed_split = speed.split(':')

for value in speed_split:

try:

# Check if it can be converted to an integer. If it can't, this will fail and Python will proceed to the "except" part

int(value)

except Exception as e:

return None

# This part below is just the function we wrote above

if len(speed_split) == 2:

minutes = int(speed_split[0]) + int(speed_split[1])/60

if len(speed_split) == 3:

minutes = 60*int(speed_split[0]) + int(speed_split[1]) + int(speed_split[2])/60

return minutes

split_columns = ['5k_split', '10k_split', '15k_split', '20k_split', '25k_split', '30k_split', '35k_split', '40k_split']

time_columns = split_columns + ['clock_time', 'net_time']

for col in time_columns:

df[f'{col}_min'] = df[col].apply(split_to_minutes)

df.head()

| div_place | name | bib | age | place | gender_place | 5k_split | 10k_split | 15k_split | 20k_split | ... | 5k_split_min | 10k_split_min | 15k_split_min | 20k_split_min | 25k_split_min | 30k_split_min | 35k_split_min | 40k_split_min | clock_time_min | net_time_min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | SAUL VISCARRA | 40402 | 15 | 382 | 352 | 22:28 | 44:00 | 1:04:56 | 1:26:24 | ... | 22.466667 | 44.000000 | 64.933333 | 86.400000 | 108.400000 | 131.533333 | 157.700000 | 181.933333 | 202.683333 | 191.850000 |

| 1 | 2 | FERNANDO GOMEZ | 40504 | 15 | 560 | 504 | 22:37 | 45:17 | 1:07:50 | 1:31:42 | ... | 22.616667 | 45.283333 | 67.833333 | 91.700000 | 115.766667 | 139.966667 | 164.583333 | 189.533333 | 203.150000 | 198.900000 |

| 2 | 3 | MARCOS GONZALEZ | 40882 | 15 | 1042 | 881 | 24:08 | 47:44 | 1:10:34 | 1:34:10 | ... | 24.133333 | 47.733333 | 70.566667 | 94.166667 | 118.666667 | 143.616667 | 174.016667 | 203.333333 | 223.583333 | 211.983333 |

| 3 | 4 | LUIS MORALES | 42286 | 13 | 1294 | 1076 | 22:50 | 46:21 | 1:11:07 | 1:34:42 | ... | 22.833333 | 46.350000 | 71.116667 | 94.700000 | 118.816667 | 144.283333 | 174.450000 | 206.366667 | 221.916667 | 217.400000 |

| 4 | 5 | PETER CASTANO | 20099 | 15 | 1413 | 1166 | 26:13 | 53:12 | 1:19:36 | 1:45:47 | ... | 26.216667 | 53.200000 | 79.600000 | 105.783333 | 131.883333 | 158.300000 | 183.633333 | 209.766667 | 225.800000 | 219.516667 |

5 rows × 27 columns

Looking good! Let’s see where None’s occurred as a result of bad values.

for col in df.columns:

missing_value_count = df[col].isna().sum()

print(f'{col} - {missing_value_count} missing')

div_place - 0 missing

name - 0 missing

bib - 0 missing

age - 0 missing

place - 0 missing

gender_place - 0 missing

5k_split - 0 missing

10k_split - 0 missing

15k_split - 0 missing

20k_split - 0 missing

25k_split - 0 missing

30k_split - 0 missing

35k_split - 0 missing

40k_split - 0 missing

clock_time - 0 missing

net_time - 0 missing

hometown - 10375 missing

5k_split_min - 4 missing

10k_split_min - 0 missing

15k_split_min - 0 missing

20k_split_min - 0 missing

25k_split_min - 0 missing

30k_split_min - 0 missing

35k_split_min - 0 missing

40k_split_min - 0 missing

clock_time_min - 0 missing

net_time_min - 0 missing

Looks like just a couple in 5k_split_min. Let’s drop and we should be good to go!

df = df.dropna(how='any', subset=['5k_split_min'])

df.shape

(10371, 27)

So we still have over 10,000 runners left to work with, that should be plenty for our purposes. With our data prepped, let’s start modeling.

Decision trees ¶

Let’s just jump right in and use sklearn’s implementation of DecisionTree. We want to predict their placing, so this is a regression problem, because we are predicting a continuous value. While placing is not really continuous (no one could get 4.3 place), there are so many possible values that it would be ridiculous to have a different category for each place. Therefore, it makes more sense to think of it as being continuous than as being categorical. Decision trees can be used for both regression and classification. They are more commonly used for classification, but we’ll start by using it for regression. To do so we will be using DecisionTreeRegressor from sklearn. Training it and making predictions with it should look exactly like how we did for linear regression. Let’s use all of our splits to predict their finishing place. We said we’ll test on 2017, but let’s still split 2016 into two sets in order to have something to tune our model with. Since 2017 is our true “test” data, it doesn’t make sense to say we’re splitting 2016 into train and “test” data. Thus subsetting the data this way is referred to as creating a “validation set”. A validation set is used to tweak your model until you’re ready to actually test it. It’s best practice to keep your test data as true test data, and not “show it” to your model before your model is ready.

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Our new split columns are named the same as the old split column, but with "_min" appended. So let's create a list of those.

split_columns_min = [f'{x}_min' for x in split_columns]

split_cols_and_age = split_columns_min + ['age']

X_train, X_valid, y_train, y_valid = train_test_split(df[split_cols_and_age], df['gender_place'], train_size=0.7)

X_train.head()

| 5k_split_min | 10k_split_min | 15k_split_min | 20k_split_min | 25k_split_min | 30k_split_min | 35k_split_min | 40k_split_min | age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2111 | 36.450000 | 68.966667 | 98.183333 | 129.983333 | 163.216667 | 203.983333 | 246.666667 | 286.816667 | 22 |

| 8256 | 27.916667 | 55.066667 | 82.016667 | 108.916667 | 139.033333 | 166.833333 | 201.250000 | 232.483333 | 46 |

| 4209 | 29.833333 | 60.433333 | 90.866667 | 123.050000 | 154.800000 | 187.750000 | 222.083333 | 255.266667 | 30 |

| 5336 | 22.366667 | 44.883333 | 67.383333 | 89.833333 | 112.233333 | 135.733333 | 166.750000 | 200.400000 | 38 |

| 11394 | 29.583333 | 60.600000 | 90.250000 | 120.016667 | 150.650000 | 181.816667 | 213.216667 | 244.083333 | 72 |

Using a decision tree in sklearn is exactly like how you’ve used all other models in sklearn! From the perspective of someone learning machine learning, one of the best features about sklearn is how consistent it is. Pretty much every model follows the same pattern:

Instantiate the model (meaning something like

lr = LinearRegression()orclf = LogisticRegression().Fit the model using

.fit()Use the model to make predictions using

.predict()(Optional) Get the score of the model (usually R^2 for regression and accuracy for classification) using

.score()

Let’s follow this same pattern here.

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeRegressor

dt_reg = DecisionTreeRegressor()

dt_reg.fit(X_train, y_train)

DecisionTreeRegressor(ccp_alpha=0.0, criterion='mse', max_depth=None,

max_features=None, max_leaf_nodes=None,

min_impurity_decrease=0.0, min_impurity_split=None,

min_samples_leaf=1, min_samples_split=2,

min_weight_fraction_leaf=0.0, presort='deprecated',

random_state=None, splitter='best')

preds = dt_reg.predict(X_valid)

for i in range(10):

print(f'Predicted: {preds[i]}, Actual: {y_valid.iloc[i]}, Diff = {preds[i]-y_valid.iloc[i]} ({100*abs(preds[i]-y_valid.iloc[i])/y_valid.iloc[i]:.2f}%)')

Predicted: 2506.0, Actual: 2545, Diff = -39.0 (1.53%)

Predicted: 800.0, Actual: 847, Diff = -47.0 (5.55%)

Predicted: 10298.0, Actual: 10197, Diff = 101.0 (0.99%)

Predicted: 8833.0, Actual: 8577, Diff = 256.0 (2.98%)

Predicted: 10989.0, Actual: 10828, Diff = 161.0 (1.49%)

Predicted: 1959.0, Actual: 1890, Diff = 69.0 (3.65%)

Predicted: 10721.0, Actual: 10694, Diff = 27.0 (0.25%)

Predicted: 1368.0, Actual: 1328, Diff = 40.0 (3.01%)

Predicted: 2193.0, Actual: 2157, Diff = 36.0 (1.67%)

Predicted: 1674.0, Actual: 1724, Diff = -50.0 (2.90%)

So most of these predictions are within a handful of percent (50-ish places) of being correct, that’s impressive! For comparison, let’s also build a linear regressor with this same data and compare the MSE from both.

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

lr = LinearRegression()

lr.fit(X_train, y_train)

LinearRegression(copy_X=True, fit_intercept=True, n_jobs=None, normalize=False)

preds_lr = lr.predict(X_valid)

for i in range(10):

print(f'Predicted: {preds_lr[i]}, Actual: {y_valid.iloc[i]}, Diff = {preds_lr[i]-y_valid.iloc[i]} ({100*abs(preds_lr[i]-y_valid.iloc[i])/y_valid.iloc[i]:.2f}%)')

Predicted: 2881.4505952084746, Actual: 2545, Diff = 336.4505952084746 (13.22%)

Predicted: 1019.8154901168928, Actual: 847, Diff = 172.81549011689276 (20.40%)

Predicted: 9987.114569245616, Actual: 10197, Diff = -209.8854307543843 (2.06%)

Predicted: 8196.702056815542, Actual: 8577, Diff = -380.29794318445784 (4.43%)

Predicted: 11653.02324126436, Actual: 10828, Diff = 825.02324126436 (7.62%)

Predicted: 2274.0219966673267, Actual: 1890, Diff = 384.0219966673267 (20.32%)

Predicted: 11318.176668353688, Actual: 10694, Diff = 624.176668353688 (5.84%)

Predicted: 1798.1529686199756, Actual: 1328, Diff = 470.1529686199756 (35.40%)

Predicted: 2442.903099096622, Actual: 2157, Diff = 285.9030990966221 (13.25%)

Predicted: 2144.7100749666715, Actual: 1724, Diff = 420.7100749666715 (24.40%)

The tree model looks to have done much better! Let’s compare R^2 and MSE to be sure.

print(f'Decision tree R^2 = {dt_reg.score(X_valid, y_valid)**2}')

print(f'Linear regression R^2 = {lr.score(X_valid, y_valid)**2}')

Decision tree R^2 = 0.9972689036020543

Linear regression R^2 = 0.9579743493585986

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error as mse

print(f'Linear regresion MSE = {mse(preds_lr, y_valid)}')

print(f'Decision Tree MSE = {mse(preds, y_valid)}')

Linear regresion MSE = 231799.09438088024

Decision Tree MSE = 14914.017030848328

That’s a huge difference!

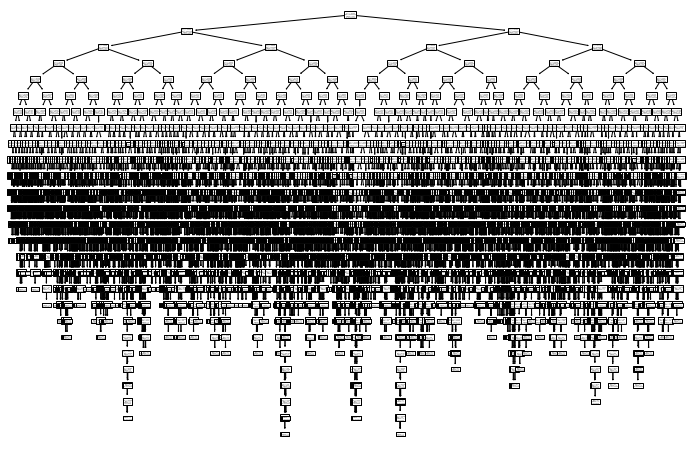

We said that a decision tree makes decisions by learning to split each leaf at a particular value. So what decisions did our tree learn to make? To answer that we can visualize our tree. sklearn has a built-in function called plot_tree. Warning: Plotting this will take a while…

from sklearn.tree import plot_tree

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

plot_tree(dt);

Overfitting and hyperparameters ¶

Woah, what happened there!? It looks like our tree is incredibly complex, with many, many different pathways and conditions. That’s not really what we want, because it’s likely the case that our model is overfitting. By overfitting we mean developing an overly complex model which does not generalize well to other scenarios. So it’s likely that the super-specific rules it learned will not apply well to 2017, nor any other year.

When building a tree there are various hyperparameters that are used to control how the tree is grown. By hyperparameters we mean the values in a model that must be chosen by the user (as opposed to being learned from the data). The most common hyperparameters for decision trees are the following:

max_depth: Controls how many levels the tree can have (somax_depth=1means only one “question” can be asked to split the tree).min_samples_split: Controls how many samples need to be seen which satisfy a rule before a new rule can be created. So if only two runners have a 5k split faster than 20 minutes (say), then by settingmin_samples_split=3(or anything bigger than 2), no new rules would be created for these runners. This helps avoid creating ultra-specific nodes which may not generalize well.max_features: How many columns can be considered. Again, this controls creating super-specific rules that require many, many columns to satisfy.

Let’s look at the depth and number of leaves of the tree we just built.

print(f'Depth = {dt.get_depth()}')

print(f'# of leaves = {dt.get_n_leaves()}')

Depth = 26

# of leaves = 7259

So our decision tree had thousands of different “rules” (i.e. leaves). Since we only had a little over 10k runners, this means most runners had their own individual rule! This is a problem, because we want to build a model that would work in general, not just on the data we trained it on. However, our tree instead learned a specific rule for every 1 or 2 runners. This could be something like “if their 5k time was less than 48 minutes and their 10k time was greater than 60 minutes and their 15k was less than… then predict 5920’th place”. This is what we mean by “overfitting”.

The way to avoid overfitting is to restrict our tree by picking hyperparameters that do not allow ultra-specific rules to be learned. Let’s try building our tree again, but starting with some very mild hyperparameter choices to avoid this phenomenon of having an overly-complex tree. To do so, you simply need to supply these hyperparameters to the decision tree when you instantiate it (step 1).

dt_simple = DecisionTreeRegressor(max_depth=3, min_samples_split=5)

dt_simple.fit(X_train, y_train)

preds_simple = dt_simple.predict(X_valid)

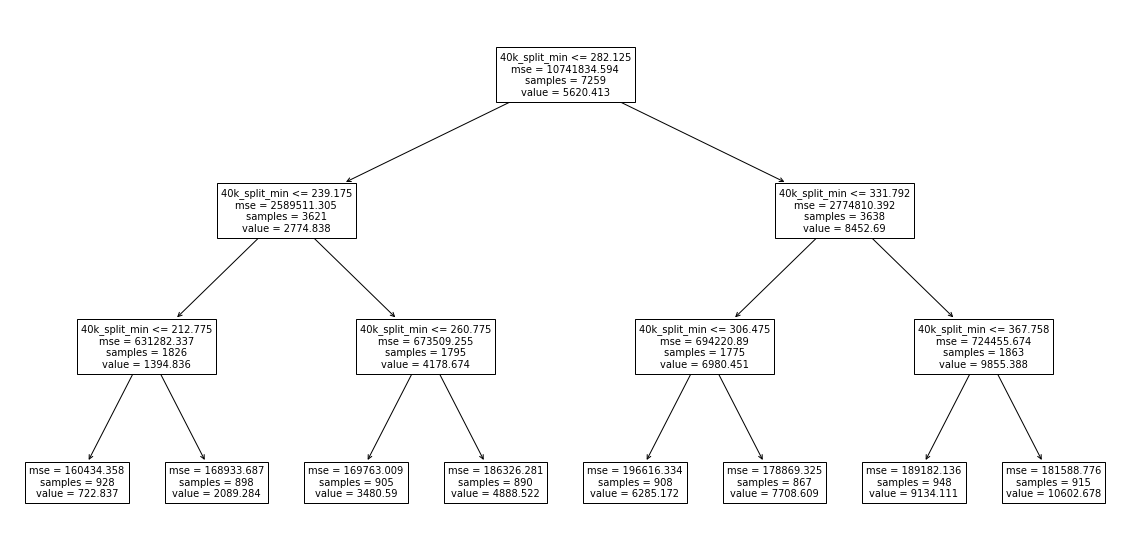

Let’s plot this decision tree as well to see what it’s like.

plt.figure(figsize=(20,10))

plot_tree(dt_simple, feature_names=split_columns_min);

So we can see that it begins by looking at the 40k_split_min time, splits it at 282.125 minutes, and then makes other decisions based on that. This seems like a more reasonable way to design a tree.

We’d like to evaluate how well our model did. We’ve been doing that by putting some print statements inside a for loop, and also computing the MSE. Rather than continuing to copy-and-paste that code, let’s create a function which does it for us.

def summarize_model(preds, actual, num_examples=10):

if isinstance(actual, pd.Series):

actual = actual.values

for i in range(num_examples):

print(f'Predicted: {preds[i]:.2f}, Actual: {actual[i]:.2f}, Diff = {preds[i]-actual[i]:.2f} ({100*abs(preds[i]-actual[i])/actual[i]:.2f}%)')

print()

print(f'MSE: {mse(preds, actual)}')

summarize_model(preds_simple, y_valid)

Predicted: 2089.28, Actual: 2545.00, Diff = -455.72 (17.91%)

Predicted: 722.84, Actual: 847.00, Diff = -124.16 (14.66%)

Predicted: 10602.68, Actual: 10197.00, Diff = 405.68 (3.98%)

Predicted: 9134.11, Actual: 8577.00, Diff = 557.11 (6.50%)

Predicted: 10602.68, Actual: 10828.00, Diff = -225.32 (2.08%)

Predicted: 2089.28, Actual: 1890.00, Diff = 199.28 (10.54%)

Predicted: 10602.68, Actual: 10694.00, Diff = -91.32 (0.85%)

Predicted: 722.84, Actual: 1328.00, Diff = -605.16 (45.57%)

Predicted: 2089.28, Actual: 2157.00, Diff = -67.72 (3.14%)

Predicted: 2089.28, Actual: 1724.00, Diff = 365.28 (21.19%)

MSE: 181762.05746029768

Not great, but we also drastically reduced the complexity of our decision tree, so that’s to be expected. Also, notice that with only a very mild tree structure, our MSE of 182,162 is still lower than the MSE from linear regression of 220,525.

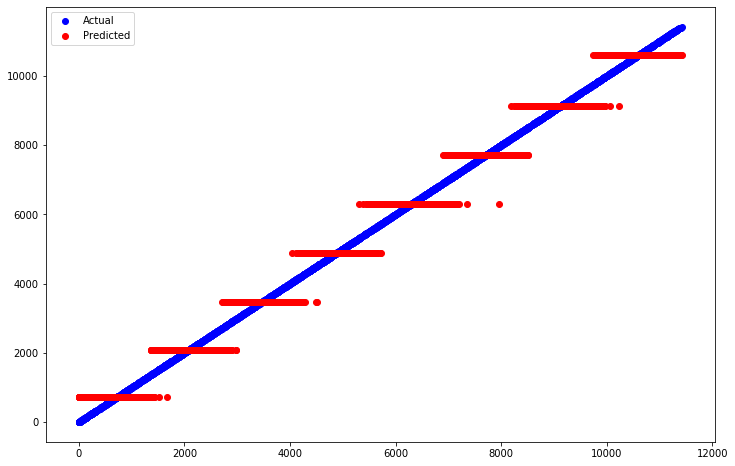

Let’s also plot the predictions made by the tree against the actual, correct values. On both the x- and y-axis we’ll put the place the person got. This might seem weird, as normally the x-axis is what we feed into our model. But since we’re feeding so many variables into our model, there’s no single one to put on the x-axis. By putting the placing on both the x- and y-axis, a perfect prediction will be a diagonal line. However, our model is not perfect, so any deviation from that will let us see what’s going on.

plt.figure(figsize=(12,8))

plt.scatter(x=y_valid, y=y_valid, color='blue', label='Actual')

plt.scatter(x=y_valid, y=preds_simple, color='red', label='Predicted')

plt.legend();

So it looks like our tree is roughly learning a step-function. In fact, if you look above at the tree diagram, you’ll see that each leaf on the bottom row tells you exactly what value it will predict for the placing for every runner who satisfied the necessary conditions to end up in that leaf. For example, to get to the first leaf on the left (starting at the top of the tree), a runner must have:

Had a 40k split of less than 282 minutes

Had a 40k split of less than 239 minutes

Had a 40k split less than 212 minutes they would be assigned a finishing place of 722. Apparently there were 928 such runners (samples). WARNING: Your numbers may vary, as decision trees involve randomness, and each run will produce new results unless

random_stateis specified when building the tree.

So wait a minute, every leaf in the tree is just looking at the 40k split! Why is that? Probably because that’s the last split just 2 kilometers before the finishing line. So obviously the top finishers would be the fastest to that point! This is an example of building a model without really thinking about your data. If you’re not careful you can easily get results which seem good, but upon closer inspection they are highly flawed.

To build a more realistic and useful model, let’s restrict ourselves to just the earlier splits to have a less-obvious problem. Let’s take the first three splits (5k, 10k and 15k), along with their age. Again, let’s first apply linear regression as a baseline. If our more complicated tree model can’t beat a simple line, then we’re doing something wrong.

# Grab just these columns in the training and validation sets

# Note that the y doesn't change, because y is just their place, nothing to do with their times

splits_5_10_15_age_cols = ['5k_split_min', '10k_split_min', '15k_split_min', 'age']

X_train_splits_5_10_15_age = X_train[splits_5_10_15_age_cols]

X_valid_splits_5_10_15_age = X_valid[splits_5_10_15_age_cols]

# Fit a linear regression model

lr_splits_5_10_15_age = LinearRegression()

lr_splits_5_10_15_age.fit(X_train_splits_5_10_15_age, y_train)

LinearRegression(copy_X=True, fit_intercept=True, n_jobs=None, normalize=False)

# Fit a decision tree

dt_splits_5_10_15_age = DecisionTreeRegressor(max_depth=3, min_samples_split=5)

dt_splits_5_10_15_age.fit(X_train_splits_5_10_15_age, y_train)

DecisionTreeRegressor(ccp_alpha=0.0, criterion='mse', max_depth=3,

max_features=None, max_leaf_nodes=None,

min_impurity_decrease=0.0, min_impurity_split=None,

min_samples_leaf=1, min_samples_split=5,

min_weight_fraction_leaf=0.0, presort='deprecated',

random_state=None, splitter='best')

# Make predictions on the validation set with both the decision tree and the linear regression model

lr_splits_5_10_15_age_preds = lr_splits_5_10_15_age.predict(X_valid_splits_5_10_15_age)

dt_splits_5_10_15_age_preds = dt_splits_5_10_15_age.predict(X_valid_splits_5_10_15_age)

# Results for linear regression

print('Linear model:')

print('='*20)

summarize_model(lr_splits_5_10_15_age_preds, y_valid)

Linear model:

====================

Predicted: 2594.78, Actual: 2545.00, Diff = 49.78 (1.96%)

Predicted: 1791.78, Actual: 847.00, Diff = 944.78 (111.54%)

Predicted: 10640.01, Actual: 10197.00, Diff = 443.01 (4.34%)

Predicted: 8094.84, Actual: 8577.00, Diff = -482.16 (5.62%)

Predicted: 6810.22, Actual: 10828.00, Diff = -4017.78 (37.11%)

Predicted: 3196.10, Actual: 1890.00, Diff = 1306.10 (69.11%)

Predicted: 10615.06, Actual: 10694.00, Diff = -78.94 (0.74%)

Predicted: 2054.87, Actual: 1328.00, Diff = 726.87 (54.73%)

Predicted: 2295.13, Actual: 2157.00, Diff = 138.13 (6.40%)

Predicted: 2694.68, Actual: 1724.00, Diff = 970.68 (56.30%)

MSE: 1674606.3773056634

# Results for the decision tree model

print('Decision tree model:')

print('='*20)

summarize_model(dt_splits_5_10_15_age_preds, y_valid)

Decision tree model:

====================

Predicted: 2168.25, Actual: 2545.00, Diff = -376.75 (14.80%)

Predicted: 779.43, Actual: 847.00, Diff = -67.57 (7.98%)

Predicted: 8884.37, Actual: 10197.00, Diff = -1312.63 (12.87%)

Predicted: 7413.37, Actual: 8577.00, Diff = -1163.63 (13.57%)

Predicted: 7413.37, Actual: 10828.00, Diff = -3414.63 (31.54%)

Predicted: 2168.25, Actual: 1890.00, Diff = 278.25 (14.72%)

Predicted: 10278.75, Actual: 10694.00, Diff = -415.25 (3.88%)

Predicted: 2168.25, Actual: 1328.00, Diff = 840.25 (63.27%)

Predicted: 2168.25, Actual: 2157.00, Diff = 11.25 (0.52%)

Predicted: 2168.25, Actual: 1724.00, Diff = 444.25 (25.77%)

MSE: 1648919.7445526074

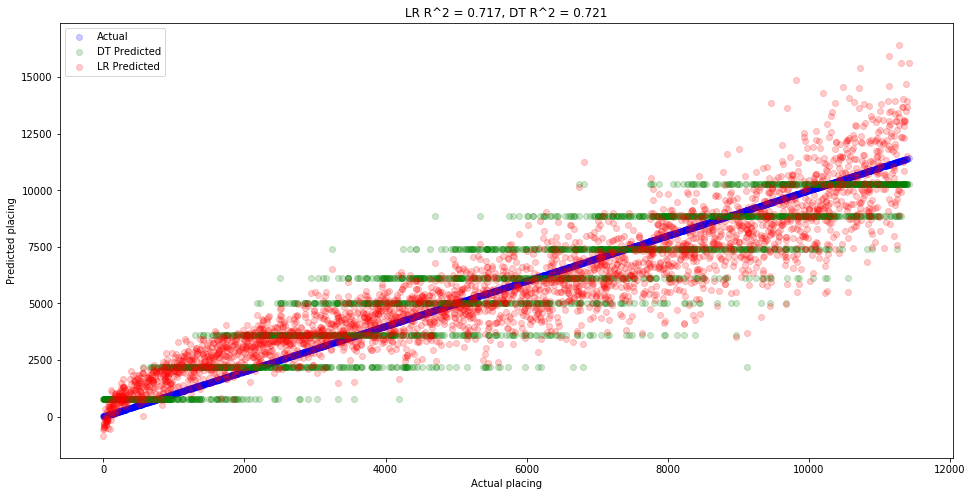

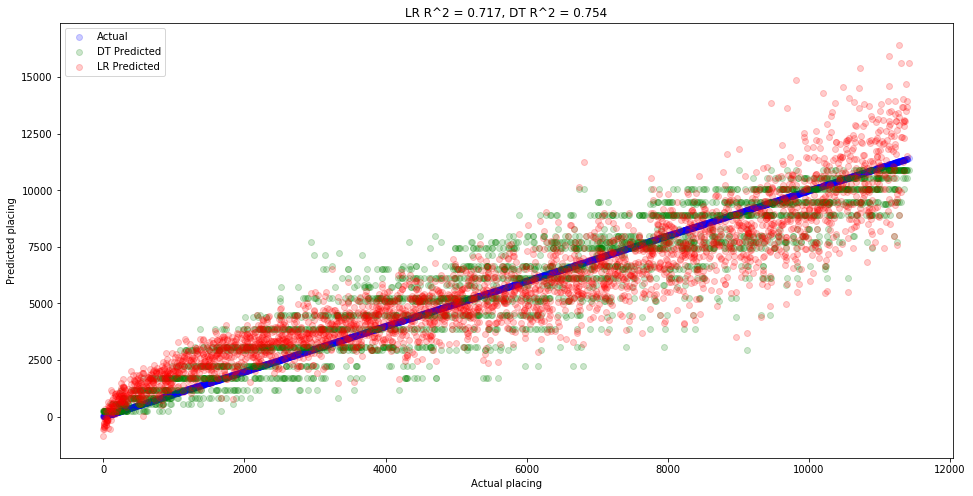

So the decision tree actually did slightly worse this time. Let’s plot the predictions of both models against the actual values to get a feel for what’s going on.

plt.figure(figsize=(16,8))

plt.scatter(x=y_valid, y=y_valid, color='blue', label='Actual', alpha=0.2)

plt.scatter(x=y_valid, y=dt_splits_5_10_15_age_preds, color='green', label='DT Predicted', alpha=0.2)

plt.scatter(x=y_valid, y=lr_splits_5_10_15_age_preds, color='red', label='LR Predicted', alpha=0.2)

plt.xlabel('Actual placing')

plt.ylabel('Predicted placing')

lr_r2 = lr_splits_5_10_15_age.score(X_valid_splits_5_10_15_age, y_valid)**2

dt_r2 = dt_splits_5_10_15_age.score(X_valid_splits_5_10_15_age, y_valid)**2

plt.title(f'LR R^2 = {lr_r2:.3f}, DT R^2 = {dt_r2:.3f}')

plt.legend();

So again we see that the decision tree (green) is approximating a step function. You can see these values by going to the diagram we printed of our decision tree and looking at the leaves on the bottom row. Each one will say value=..., which is the value that gets assigned to that entire leaf. This is why decision trees are more often used for classification then regression. That’s because regression typically involves continuous values, whereas decision trees produce decidedly non-continuous step functions. Having said that, decision trees are extremely powerful and should not be overlooked for any type of problem.

Let’s build one last decision tree, this time with a medium-level of depth and complexity. The point is to see how complex our tree needs to be before it outpeforms linear regression.

# Create our tree

dt_splits_5_10_15_age2 = DecisionTreeRegressor(max_depth=5, min_samples_split=5)

# Train our tree

dt_splits_5_10_15_age2.fit(X_train_splits_5_10_15_age, y_train)

# Make predictions with our tree

dt_splits_5_10_15_age_preds2 = dt_splits_5_10_15_age2.predict(X_valid_splits_5_10_15_age)

# Compare predictions to linear regression

print('Linear model:')

print('='*20)

summarize_model(lr_splits_5_10_15_age_preds, y_valid)

print('Decision tree model:')

print('='*20)

summarize_model(dt_splits_5_10_15_age_preds2, y_valid)

# R^2

lr_r2 = lr_splits_5_10_15_age.score(X_valid_splits_5_10_15_age, y_valid)**2 # Same as above

dt_r2 = dt_splits_5_10_15_age2.score(X_valid_splits_5_10_15_age, y_valid)**2

# Plot the predictions

plt.figure(figsize=(16,8))

plt.scatter(x=y_valid, y=y_valid, color='blue', label='Actual', alpha=0.2)

plt.scatter(x=y_valid, y=dt_splits_5_10_15_age_preds2, color='green', label='DT Predicted', alpha=0.2)

plt.scatter(x=y_valid, y=lr_splits_5_10_15_age_preds, color='red', label='LR Predicted', alpha=0.2)

plt.xlabel('Actual placing')

plt.ylabel('Predicted placing')

plt.title(f'LR R^2 = {lr_r2:.3f}, DT R^2 = {dt_r2:.3f}')

plt.legend();

Linear model:

====================

Predicted: 2594.78, Actual: 2545.00, Diff = 49.78 (1.96%)

Predicted: 1791.78, Actual: 847.00, Diff = 944.78 (111.54%)

Predicted: 10640.01, Actual: 10197.00, Diff = 443.01 (4.34%)

Predicted: 8094.84, Actual: 8577.00, Diff = -482.16 (5.62%)

Predicted: 6810.22, Actual: 10828.00, Diff = -4017.78 (37.11%)

Predicted: 3196.10, Actual: 1890.00, Diff = 1306.10 (69.11%)

Predicted: 10615.06, Actual: 10694.00, Diff = -78.94 (0.74%)

Predicted: 2054.87, Actual: 1328.00, Diff = 726.87 (54.73%)

Predicted: 2295.13, Actual: 2157.00, Diff = 138.13 (6.40%)

Predicted: 2694.68, Actual: 1724.00, Diff = 970.68 (56.30%)

MSE: 1674606.3773056634

Decision tree model:

====================

Predicted: 1723.91, Actual: 2545.00, Diff = -821.09 (32.26%)

Predicted: 1182.63, Actual: 847.00, Diff = 335.63 (39.63%)

Predicted: 9469.34, Actual: 10197.00, Diff = -727.66 (7.14%)

Predicted: 7719.15, Actual: 8577.00, Diff = -857.85 (10.00%)

Predicted: 7719.15, Actual: 10828.00, Diff = -3108.85 (28.71%)

Predicted: 2252.04, Actual: 1890.00, Diff = 362.04 (19.16%)

Predicted: 10065.15, Actual: 10694.00, Diff = -628.85 (5.88%)

Predicted: 1723.91, Actual: 1328.00, Diff = 395.91 (29.81%)

Predicted: 1723.91, Actual: 2157.00, Diff = -433.09 (20.08%)

Predicted: 1723.91, Actual: 1724.00, Diff = -0.09 (0.01%)

MSE: 1440131.3709699702

We’ve learned a valuable lesson in this notebook, which is that just because a model gives better results, doesn’t mean it’s a better model. We saw this with the decision tree, where it gave great predictions, but the tree itself was so complicated that it seemed unrealistic. Does it really make sense to have a model which requires most individuals to have their own custom rule. This leads to overfitting, which means models that don’t generalize well. In the future, we’ll look at our data more closely before just blindly picking a model to apply.

The mathematics of decision trees ¶

While we’ve now discussed what a decision tree is, there is still the question of how a decision tree is made. How is it that sklearn decides which column to look at first, and what the cutoff should be? Let’s go back to the Titanic data to understand this.

df = pd.read_csv(drive_dir + 'data/titanic.csv')

df.head()

| PassengerId | Survived | Pclass | Name | Sex | Age | SibSp | Parch | Ticket | Fare | Cabin | Embarked | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | Braund, Mr. Owen Harris | male | 22.0 | 1 | 0 | A/5 21171 | 7.2500 | NaN | S |

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Cumings, Mrs. John Bradley (Florence Briggs Th... | female | 38.0 | 1 | 0 | PC 17599 | 71.2833 | C85 | C |

| 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | Heikkinen, Miss. Laina | female | 26.0 | 0 | 0 | STON/O2. 3101282 | 7.9250 | NaN | S |

| 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | Futrelle, Mrs. Jacques Heath (Lily May Peel) | female | 35.0 | 1 | 0 | 113803 | 53.1000 | C123 | S |

| 4 | 5 | 0 | 3 | Allen, Mr. William Henry | male | 35.0 | 0 | 0 | 373450 | 8.0500 | NaN | S |

Let’s build a decision tree classifier to predict the survival. We’ll then examine the tree and learn step-by-step how it was created. Let’s start by preparing our data, including dropping missing values nad label encoding any object columns so that all values are numbers.

# Drop any rows with missing values

df = df.dropna(how='any')

# Columns we'll actually use (things like "Name" are probably useless)

X_cols = ['Pclass', 'Sex', 'Age', 'SibSp', 'Parch', 'Fare', 'Embarked']

y_col = 'Survived'

df[X_cols].dtypes

Pclass int64

Sex object

Age float64

SibSp int64

Parch int64

Fare float64

Embarked object

dtype: object

object_cols = ['Sex', 'Embarked']

# Save the label encoders here so that we can use them later if we want to go back to the original text

label_encoders = {}

for c in object_cols:

le = LabelEncoder()

df[c] = le.fit_transform(df[c])

label_encoders[c] = le

# Split the data into training and testing data

train_df, test_df = train_test_split(df)

X_train = train_df[X_cols]

y_train = train_df[y_col]

X_test = test_df[X_cols]

y_test = test_df[y_col]

Now we can build our classification tree.

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier

dt_clf = DecisionTreeClassifier(max_depth=3, min_samples_split=5)

dt_clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

DecisionTreeClassifier(ccp_alpha=0.0, class_weight=None, criterion='gini',

max_depth=3, max_features=None, max_leaf_nodes=None,

min_impurity_decrease=0.0, min_impurity_split=None,

min_samples_leaf=1, min_samples_split=5,

min_weight_fraction_leaf=0.0, presort='deprecated',

random_state=None, splitter='best')

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

plot_tree(dt_clf, feature_names=X_train.columns, class_names=['Died', 'Survived']);

A decision tree makes its decision by trying to find which feature is the most important at each step. Let’s think about how we could do this. Suppose that all the passengers on the Titanic were males (obviously this wasn’t the case, but just bear with me). Then checking whether or not someone was a male would be useless, as it wouldn’t tell us anything. Similarly, if all but just, say, five were males, then that too is not useful. Even if it ended up all females survived, then we’ve only concluded something about five passengers. Therefore, our first task is to choose a feature that has an even balance of samples. If your feature has more than one possible value (like how PClass can be 1, 2, or 3, or how Fare can be any real number), then we also consider a cutoff. So we would want to choose a cutoff for Fare so that there is an even balance of people on each side of the cutoff. For instance, perhaps half the people had a fare more than $20, and half had a fare greater than or equal to $20. Then $20 would be our cutoff.

Let’s start with the entire dataset and see what percentage survived.

df['Survived'].value_counts(normalize=True)

1 0.672131

0 0.327869

Name: Survived, dtype: float64

So about 67.2% of the passengers died, and the remaining 32.8% survived. Suppose you picked a random passenger about which you know nothing whatsoever. You are asked to guess whether or not they died. The best we can do is guess “died” 67.2% of the time, and guess “survived” 32.8% of the time, since that’s all the information we know. If we did so, how often would we be wrong?

Event |

Probability |

Guessed correct? |

|---|---|---|

Guess survived, actually survived |

0.672 * 0.672 = 0.452 (prob. we guess survived * prob. they actually survived) |

Yes |

Guess survived, actually died |

0.672 * 0.328 = 0.220 (prob. we guess survived * prob. they actually died) |

No |

Guess died, actually survived |

0.328 * 0.672 = 0.220 |

No |

Guess died, actually died |

0.328 * 0.328 = 0.107 |

Yes |

So we would have guessed incorrectly 0.220 + 0.220 = 0.440 = 44.0% of the time. Not bad, but can we do better if, rather than looking at the entire dataset, we instead split up the data? Let’s split it up by males and females, and consider each separately.

sex_le = label_encoders['Sex']

males_df = df[df['Sex'] == sex_le.transform(['male'])[0]]

females_df = df[df['Sex'] == sex_le.transform(['female'])[0]]

males_df.head()

| PassengerId | Survived | Pclass | Name | Sex | Age | SibSp | Parch | Ticket | Fare | Cabin | Embarked | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 7 | 0 | 1 | McCarthy, Mr. Timothy J | 1 | 54.0 | 0 | 0 | 17463 | 51.8625 | E46 | 2 |

| 21 | 22 | 1 | 2 | Beesley, Mr. Lawrence | 1 | 34.0 | 0 | 0 | 248698 | 13.0000 | D56 | 2 |

| 23 | 24 | 1 | 1 | Sloper, Mr. William Thompson | 1 | 28.0 | 0 | 0 | 113788 | 35.5000 | A6 | 2 |

| 27 | 28 | 0 | 1 | Fortune, Mr. Charles Alexander | 1 | 19.0 | 3 | 2 | 19950 | 263.0000 | C23 C25 C27 | 2 |

| 54 | 55 | 0 | 1 | Ostby, Mr. Engelhart Cornelius | 1 | 65.0 | 0 | 1 | 113509 | 61.9792 | B30 | 0 |

females_df.head()

| PassengerId | Survived | Pclass | Name | Sex | Age | SibSp | Parch | Ticket | Fare | Cabin | Embarked | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Cumings, Mrs. John Bradley (Florence Briggs Th... | 0 | 38.0 | 1 | 0 | PC 17599 | 71.2833 | C85 | 0 |

| 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | Futrelle, Mrs. Jacques Heath (Lily May Peel) | 0 | 35.0 | 1 | 0 | 113803 | 53.1000 | C123 | 2 |

| 10 | 11 | 1 | 3 | Sandstrom, Miss. Marguerite Rut | 0 | 4.0 | 1 | 1 | PP 9549 | 16.7000 | G6 | 2 |

| 11 | 12 | 1 | 1 | Bonnell, Miss. Elizabeth | 0 | 58.0 | 0 | 0 | 113783 | 26.5500 | C103 | 2 |

| 52 | 53 | 1 | 1 | Harper, Mrs. Henry Sleeper (Myna Haxtun) | 0 | 49.0 | 1 | 0 | PC 17572 | 76.7292 | D33 | 0 |

What percentage of each group survived?

males_df['Survived'].value_counts(normalize=True)

0 0.568421

1 0.431579

Name: Survived, dtype: float64

females_df['Survived'].value_counts(normalize=True)

1 0.931818

0 0.068182

Name: Survived, dtype: float64

Let’s do the same calculations as above to find the probability of guessing wrong. But this time, rather than looking at what percentage of the entire set of passengers survived/died, we’ll deal with men and women separately.

Men only

Event |

Probability |

Guessed correct? |

|---|---|---|

Guess survived, actually survived |

0.432 * 0.432 = 0.187 |

Yes |

Guess survived, actually died |

0.432 * 0.568 = 0.245 |

No |

Guess died, actually survived |

0.568 * 0.432 = 0.245 |

No |

Guess died, actually died |

0.568 * 0.568 = 0.323 |

Yes |

Women only

Event |

Probability |

Guessed correct? |

|---|---|---|

Guess survived, actually survived |

0.068 * 0.068 = 0.005 |

Yes |

Guess survived, actually died |

0.068 * 0.932 = 0.063 |

No |

Guess died, actually survived |

0.932 * 0.068 = 0.063 |

No |

Guess died, actually died |

0.932 * 0.932 = 0.869 |

Yes |

So for men only we guessed incorrectly 0.245 + 0.245 = 0.490 = 49.0% of the time, and for women only we guessed incorrectly 0.063 + 0.063 = 0.126 = 12.6% of the time.

Is this better than looking at the whole dataset? It’s a little tricky to tell at first glance, because now we have two percentages, as opposed to just the single percentage of incorrectness we had when we looked at the entire dataset. You may be tempted to average these two percentages and say that we were incorrect (49.0% + 12.6%) / 2 = 30.8% of the time. But that would assume that there are an equal number of men and women. Instead, we’ll take the weighted average of how many of each sex were on board. Let’s check how many of each sex were on board.

df['Sex'].value_counts()

1 95

0 88

Name: Sex, dtype: int64

Looking at the DataFrames above we see that males have a sex value of 1 and females of 0. So there were 95 males and 88 females. Thus there were 95 + 88 = 183 total passengers. Therefore the weighted average for incorrect guesses is given by

Thus we expect to guess incorrectly about 31.5% of the time. This is indeed an improvement above looking at the entire dataset, for which we would have guessed incorrectly 44.0% of the time.

So is Sex the “best” column? Following the ideas above, we can define “best” as the column which causes us to guess incorrectly least often. Rather than repeatedly doing this by hand, let’s write a function to do this work for us. Note that if we use a column like Fare which has many different values, we’ll also need to supply a cutoff. So we could (say) split up our passengers by those who paid more or less than \$20.

def pct_guess_incorrectly(df, col, cutoff):

# Split up the data according to the cutoff

df_lower = df[df[col] < cutoff]

df_upper = df[df[col] >= cutoff]

# Find the percentage of survived and died for each subset

lower_died_pct = df_lower[df_lower['Survived'] == 0].shape[0] / df_lower.shape[0]

upper_died_pct = df_upper[df_upper['Survived'] == 0].shape[0] / df_upper.shape[0]

lower_survived_pct = 1 - lower_died_pct

upper_survived_pct = 1 - upper_died_pct

# Find the percentage of incorrect guesses for each subsets

# Prob we picked died * prob they survived + prob we picked survived * prob they died

lower_incorrect_pct = lower_died_pct*lower_survived_pct + lower_survived_pct*lower_died_pct

upper_incorrect_pct = upper_died_pct*upper_survived_pct + upper_survived_pct*upper_died_pct

# Find what percentage of the people were in the upper and lower subsets

pct_lower = df_lower.shape[0] / df.shape[0]

pct_upper = df_upper.shape[0] / df.shape[0]

# Compute the weighted average

pct_incorrect = pct_lower * lower_incorrect_pct + pct_upper * upper_incorrect_pct

return pct_incorrect

Let’s double-check that our function is giving the same values as we computed by hand for Sex.

# Since male == 1 and female == 0, we'll use a cutoff of 0.5 to split them up

# In fact, any number strictly between 0 and 1 would work just fine

pct_guess_incorrectly(df, 'Sex', 0.5)

0.31580516118911284

Looks good! Let’s now try Pclass. We don’t know what the cutoff should be (the passenger classes are 1, 2, and 3, so we need to put a cutoff to split them up). We could pick a cutoff that puts all of the passenger classes together, such as cutoff=0. We could pick a cutoff which splits class 1 off, such as cutoff=1.5, and so forth. Let’s just compute it for each of them and see what cutoff gives the lowest chance of guessing incorrectly.

# An error is coming...

pclass_cutoffs = [0, 1.5, 2.5, 3.5]

for cutoff in pclass_cutoffs:

cutoff_pct_incorrect = pct_guess_incorrectly(df, 'Pclass', cutoff)

print(f'Cutoff = {cutoff}, % incorrect = {100*cutoff_pct_incorrect:.2f}%')

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

ZeroDivisionError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-162-90fc85e86a0b> in <module>

3

4 for cutoff in pclass_cutoffs:

----> 5 cutoff_pct_incorrect = pct_guess_incorrectly(df, 'Pclass', cutoff)

6 print(f'Cutoff = {cutoff}, % incorrect = {100*cutoff_pct_incorrect:.2f}%')

<ipython-input-158-21b216d99eb0> in pct_guess_incorrectly(df, col, cutoff)

5

6 # Find the percentage of survived and died for each subset

----> 7 lower_died_pct = df_lower[df_lower['Survived'] == 0].shape[0] / df_lower.shape[0]

8 upper_died_pct = df_upper[df_upper['Survived'] == 0].shape[0] / df_upper.shape[0]

9 lower_survived_pct = 1 - lower_died_pct

ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

Uh-oh, it looks like we’re dividing by zero somewhere! Why would this be? What’s happening is that (at least) one of our cutoffs is producing an empty subset of passengers. For example, there are no passengesr with a Pclass < 0. We didn’t take this into account when we wrote our function, so let’s fix it now by telling the user if they picked a bad cutoff.

def pct_guess_incorrectly(df, col, cutoff):

# Split up the data according to the cutoff

df_lower = df[df[col] < cutoff]

df_upper = df[df[col] >= cutoff]

# If either of these subsets is empty, set the percentages to zero

if df_lower.shape[0] == 0 or df_upper.shape[0] == 0:

print(f'Cutoff of {cutoff} for column {col} produced an empty subset, change the cutoff')

return None

# Find the percentage of survived and died for each subset

lower_died_pct = df_lower[df_lower['Survived'] == 0].shape[0] / df_lower.shape[0]

upper_died_pct = df_upper[df_upper['Survived'] == 0].shape[0] / df_upper.shape[0]

lower_survived_pct = 1 - lower_died_pct

upper_survived_pct = 1 - upper_died_pct

# Find the percentage of incorrect guesses for each subsets

# Prob we picked died * prob they survived + prob we picked survived * prob they died

lower_incorrect_pct = lower_died_pct*lower_survived_pct + lower_survived_pct*lower_died_pct

upper_incorrect_pct = upper_died_pct*upper_survived_pct + upper_survived_pct*upper_died_pct

# Find what percentage of the people were in the upper and lower subsets

pct_lower = df_lower.shape[0] / df.shape[0]

pct_upper = df_upper.shape[0] / df.shape[0]

# Compute the weighted average

pct_incorrect = pct_lower * lower_incorrect_pct + pct_upper * upper_incorrect_pct

return pct_incorrect

pclass_cutoffs = [0, 1.5, 2.5, 3.5]

for cutoff in pclass_cutoffs:

cutoff_pct_incorrect = pct_guess_incorrectly(df, 'Pclass', cutoff)

if cutoff_pct_incorrect is not None:

print(f'Cutoff = {cutoff}, % incorrect = {100*cutoff_pct_incorrect:.2f}%')

Cutoff of 0 for column Pclass produced an empty subset, change the cutoff

Cutoff = 1.5, % incorrect = 44.07%

Cutoff = 2.5, % incorrect = 43.73%

Cutoff of 3.5 for column Pclass produced an empty subset, change the cutoff

So it looks like grouping by passenger class is not an improvement over grouping by sex. Let’s try Fare next. Since there are so many possible fares, we’ll just create a really big list of cutoffs and let the code find which one is best. The simplest way to create a big list of evenly spaced points is to use linspace() from numpy. This creates linearly spaced points (hence the name). It wants to know the starting and ending points, and how many points you want in-between. Here’s an example:

# Starts at 0, ends at 5, creates 10 evenly spaced points in-between

np.linspace(0, 5, 10)

array([0. , 0.55555556, 1.11111111, 1.66666667, 2.22222222,

2.77777778, 3.33333333, 3.88888889, 4.44444444, 5. ])

# Create cutoffs for the entire range of fares, and generate 1000 different cutoffs

fare_cutoffs = np.linspace(df['Fare'].min(), df['Fare'].max(), 1000)

# Keep track of what cutoff produced the lowest percentage of incorrect guesses

best_pct_incorrect = 1

best_cutoff = None

# Go through all cutoffs

for cutoff in fare_cutoffs:

cutoff_pct_incorrect = pct_guess_incorrectly(df, 'Fare', cutoff)

# Check if it worked (didn't return a None), and if the % incorrect is lower than what we've seen so far

if cutoff_pct_incorrect is not None and cutoff_pct_incorrect < best_pct_incorrect:

# If so, save it

best_pct_incorrect = cutoff_pct_incorrect

best_cutoff = cutoff

# Print out the results

print(f'Best cutoff = {best_cutoff:.3f} had a % incorrect of {100*best_pct_incorrect:.2f}%')

Cutoff of 0.0 for column Fare produced an empty subset, change the cutoff

Best cutoff = 7.693 had a % incorrect of 41.01%

So a cutoff of $7.69 produced the best outcome with 41.01% of the guesses being incorrect. This is still worse than we got with the Sex column.

Certainly we could repeat this for all columns, but hopefully at this point you get the idea. In fact, Sex will produce the best results, as we know by looking at the decision tree we built! The decision trees go through this process for all columns and for all possible cutoffs. It then picks which one got the best result (lower percentage chance of guessing incorrectly) and chooses that as the first node. It then repeats this process for each node in the tree until the specificied max_depth is reached.

The value we have been calling “percentage guessed incorrectly” is really called the Gini impurity. If you look at the sklearn decision tree documentation you will see a parameter called “criterion”, which has a default value of “gini”. This means that the criteria it uses to form the tree is Gini impurity. You now understand how decision trees work!

Exercises¶

Grab another dataset and make your own decision trees. How do changing the hyperparameters affect the result?

Write a function which goes through all possible columns and all cutoffs and finds which gives the best (lowest) Gini impurity.

In the sklearn decision tree documentation there are many other hyperparameters you can choose. Read about them and try playing with them.