Nearest neighbors¶

Last week we learned about logistic regression. This was the first classification technique we learned. However, one limitation of logistic regression is that the input variables must be continuous. What can we do if we have categorical variables that we want to train our model with? One model that handles categorical variables as well as continuous variables is nearest neighbors. This week we will learn about nearest neighbors, along with other ways to deal with categorical variables.

Imports¶

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.preprocessing import LabelEncoder

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression, LinearRegression

from sklearn.metrics import classification_report

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

Data loading¶

In this notebook we will continue working with data from an Internet Service Provider (ISP). Below is a brief refresher on some of the columns.

customerID: A unique ID for each customer

Partner: Whether or not the customer has a partner (spouse/significant other)

tenure: How many months the person has been a customer

MonthlyCharges: How much (in dollars) the customer is charged every month

TotalCharges: How much the customer has been charged over their lifetime with the ISP

Churn: Whether or not a customer leaves the ISP (i.e. cancels their service)

df = pd.read_csv('data/isp_customers.csv')

df.head()

| customerID | gender | SeniorCitizen | Partner | Dependents | tenure | PhoneService | MultipleLines | InternetService | OnlineSecurity | ... | DeviceProtection | TechSupport | StreamingTV | StreamingMovies | Contract | PaperlessBilling | PaymentMethod | MonthlyCharges | TotalCharges | Churn | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7590-VHVEG | Female | 0 | Yes | No | 1 | No | No phone service | DSL | No | ... | No | No | No | No | Month-to-month | Yes | Electronic check | 29.85 | 29.85 | No |

| 1 | 5575-GNVDE | Male | 0 | No | No | 34 | Yes | No | DSL | Yes | ... | Yes | No | No | No | One year | No | Mailed check | 56.95 | 1889.5 | No |

| 2 | 3668-QPYBK | Male | 0 | No | No | 2 | Yes | No | DSL | Yes | ... | No | No | No | No | Month-to-month | Yes | Mailed check | 53.85 | 108.15 | Yes |

| 3 | 7795-CFOCW | Male | 0 | No | No | 45 | No | No phone service | DSL | Yes | ... | Yes | Yes | No | No | One year | No | Bank transfer (automatic) | 42.30 | 1840.75 | No |

| 4 | 9237-HQITU | Female | 0 | No | No | 2 | Yes | No | Fiber optic | No | ... | No | No | No | No | Month-to-month | Yes | Electronic check | 70.70 | 151.65 | Yes |

5 rows × 21 columns

We’ll do the same cleaning as we did last week.

df['TotalCharges'] = pd.to_numeric(df['TotalCharges'], errors='coerce')

df = df.dropna(how='any')

Label encoding¶

Most machine learning models only work with numerical data. It is fine for the numerical data to be categorical, but it must be numerical. Therefore, almost no model can work with vlaues like “Female” or “No phone service”. Therefore the first step when dealing with categorical data is to “encode” your categorical data to make it numerical. All that encoding is is changing data to numbers. Let’s encode the gender column first. We’ll do this “by hand”, and later do it in a more efficient way using sklearn.

The simplest “by hand” way to encode data is to make a Python dictionary which maps the text values to numerical values. So for example, we could set Female to be 0 and Male to be 1.

gender_map = {'Female': 0, 'Male': 1}

We can then use the Pandas .map() function. This takes in a dictionary (or a function) and applies is to every row. It then replaces the value in that row with the result from the function, or the value in the dictionary. That may sound complicated, but it’s actually very simple. By supplying .map() with the gender_map above for the column gender, it will replace every 'Female' with 0 and every 'Male' with '1'.

df['gender'] = df['gender'].map(gender_map)

df.head()

| customerID | gender | SeniorCitizen | Partner | Dependents | tenure | PhoneService | MultipleLines | InternetService | OnlineSecurity | ... | DeviceProtection | TechSupport | StreamingTV | StreamingMovies | Contract | PaperlessBilling | PaymentMethod | MonthlyCharges | TotalCharges | Churn | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7590-VHVEG | 0 | 0 | Yes | No | 1 | No | No phone service | DSL | No | ... | No | No | No | No | Month-to-month | Yes | Electronic check | 29.85 | 29.85 | No |

| 1 | 5575-GNVDE | 1 | 0 | No | No | 34 | Yes | No | DSL | Yes | ... | Yes | No | No | No | One year | No | Mailed check | 56.95 | 1889.50 | No |

| 2 | 3668-QPYBK | 1 | 0 | No | No | 2 | Yes | No | DSL | Yes | ... | No | No | No | No | Month-to-month | Yes | Mailed check | 53.85 | 108.15 | Yes |

| 3 | 7795-CFOCW | 1 | 0 | No | No | 45 | No | No phone service | DSL | Yes | ... | Yes | Yes | No | No | One year | No | Bank transfer (automatic) | 42.30 | 1840.75 | No |

| 4 | 9237-HQITU | 0 | 0 | No | No | 2 | Yes | No | Fiber optic | No | ... | No | No | No | No | Month-to-month | Yes | Electronic check | 70.70 | 151.65 | Yes |

5 rows × 21 columns

That’s it! We can do the same thing for any column we want. If you want to avoid typing all values by hand (perhaps there are dozens of them, or perhaps each one is very long), you can also use enumerate to save you time. What enumerate does is return each item in a list, along with a counter. Here’s an example:

for x, y in enumerate(['a', 'b', 'c']):

print(x, y)

0 a

1 b

2 c

As you can see, the first thing enumerate returns is the counter. The first item is in the zeroth place, so it returns a zero. It also returns what that item is ('a' in our case). It then repeats this for all items.

We can use this to our advantage to make our own maps without having to write out all items by hand. Let’s do this for the column MultipleLines.

multiple_lines_map = {item: i for i, item in enumerate(df['MultipleLines'].unique())}

multiple_lines_map

{'No phone service': 0, 'No': 1, 'Yes': 2}

Breaking this down, we first enumerate all the unique values in the column MultipleLines. Then, enumerate returns two things: the counter (which we called i) and the item (which we called item). We then using comprehension to make a dictionary. The key is the item, and the value is the counter. Try doing it for other columns!

df['MultipleLines'] = df['MultipleLines'].map(multiple_lines_map)

df.head()

| customerID | gender | SeniorCitizen | Partner | Dependents | tenure | PhoneService | MultipleLines | InternetService | OnlineSecurity | ... | DeviceProtection | TechSupport | StreamingTV | StreamingMovies | Contract | PaperlessBilling | PaymentMethod | MonthlyCharges | TotalCharges | Churn | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7590-VHVEG | 0 | 0 | Yes | No | 1 | No | 0 | DSL | No | ... | No | No | No | No | Month-to-month | Yes | Electronic check | 29.85 | 29.85 | No |

| 1 | 5575-GNVDE | 1 | 0 | No | No | 34 | Yes | 1 | DSL | Yes | ... | Yes | No | No | No | One year | No | Mailed check | 56.95 | 1889.50 | No |

| 2 | 3668-QPYBK | 1 | 0 | No | No | 2 | Yes | 1 | DSL | Yes | ... | No | No | No | No | Month-to-month | Yes | Mailed check | 53.85 | 108.15 | Yes |

| 3 | 7795-CFOCW | 1 | 0 | No | No | 45 | No | 0 | DSL | Yes | ... | Yes | Yes | No | No | One year | No | Bank transfer (automatic) | 42.30 | 1840.75 | No |

| 4 | 9237-HQITU | 0 | 0 | No | No | 2 | Yes | 1 | Fiber optic | No | ... | No | No | No | No | Month-to-month | Yes | Electronic check | 70.70 | 151.65 | Yes |

5 rows × 21 columns

While this works great, it has some problems. One problem is that if you have to keep track of what a gender of 0 means, what a MultipleLines of 2 means, and so forth. Also, if you wanted to go backwards (i.e. turn MultipleLines = 0 into 'No phone service'), you would need to make a reverse map that turns the numbers back into text. This is totally do-able, but a bit annoying.

Luckily, sklearn has a helper function (surprise!) to help with this. It is called a LabelEncoder. A label encoder just does what we did, but it handles all of these steps for us. In order to use a LabelEncoder, you must .fit() it on the data you want to encode (so likely df['my_column']). It can then .transform() a column to turn text into numbers. It can also .inverse_transform() to turn numbers back into text. Let’s try it.

contract_le = LabelEncoder()

contract_le.fit(df['Contract'])

df['Contract'] = contract_le.transform(df['Contract'])

df.head()

| customerID | gender | SeniorCitizen | Partner | Dependents | tenure | PhoneService | MultipleLines | InternetService | OnlineSecurity | ... | DeviceProtection | TechSupport | StreamingTV | StreamingMovies | Contract | PaperlessBilling | PaymentMethod | MonthlyCharges | TotalCharges | Churn | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7590-VHVEG | 0 | 0 | Yes | No | 1 | No | 0 | DSL | No | ... | No | No | No | No | 0 | Yes | Electronic check | 29.85 | 29.85 | No |

| 1 | 5575-GNVDE | 1 | 0 | No | No | 34 | Yes | 1 | DSL | Yes | ... | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | No | Mailed check | 56.95 | 1889.50 | No |

| 2 | 3668-QPYBK | 1 | 0 | No | No | 2 | Yes | 1 | DSL | Yes | ... | No | No | No | No | 0 | Yes | Mailed check | 53.85 | 108.15 | Yes |

| 3 | 7795-CFOCW | 1 | 0 | No | No | 45 | No | 0 | DSL | Yes | ... | Yes | Yes | No | No | 1 | No | Bank transfer (automatic) | 42.30 | 1840.75 | No |

| 4 | 9237-HQITU | 0 | 0 | No | No | 2 | Yes | 1 | Fiber optic | No | ... | No | No | No | No | 0 | Yes | Electronic check | 70.70 | 151.65 | Yes |

5 rows × 21 columns

The Contract column has been converted into text. What if we want to go backwards?

df['Contract'] = contract_le.inverse_transform(df['Contract'])

df.head()

| customerID | gender | SeniorCitizen | Partner | Dependents | tenure | PhoneService | MultipleLines | InternetService | OnlineSecurity | ... | DeviceProtection | TechSupport | StreamingTV | StreamingMovies | Contract | PaperlessBilling | PaymentMethod | MonthlyCharges | TotalCharges | Churn | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7590-VHVEG | 0 | 0 | Yes | No | 1 | No | 0 | DSL | No | ... | No | No | No | No | Month-to-month | Yes | Electronic check | 29.85 | 29.85 | No |

| 1 | 5575-GNVDE | 1 | 0 | No | No | 34 | Yes | 1 | DSL | Yes | ... | Yes | No | No | No | One year | No | Mailed check | 56.95 | 1889.50 | No |

| 2 | 3668-QPYBK | 1 | 0 | No | No | 2 | Yes | 1 | DSL | Yes | ... | No | No | No | No | Month-to-month | Yes | Mailed check | 53.85 | 108.15 | Yes |

| 3 | 7795-CFOCW | 1 | 0 | No | No | 45 | No | 0 | DSL | Yes | ... | Yes | Yes | No | No | One year | No | Bank transfer (automatic) | 42.30 | 1840.75 | No |

| 4 | 9237-HQITU | 0 | 0 | No | No | 2 | Yes | 1 | Fiber optic | No | ... | No | No | No | No | Month-to-month | Yes | Electronic check | 70.70 | 151.65 | Yes |

5 rows × 21 columns

And we’re back!

Let’s write a for loop to go through the columns we want to encode. We’ll save each of the encoders into a dictionary so that we can access it later if we need it.

cat_cols = ['Partner', 'Dependents', 'PhoneService', 'InternetService', 'Contract', 'PaymentMethod', 'Churn']

label_encoder = {}

# Go through each categorical column

for c in cat_cols:

# Create a new label encoder for this column

le = LabelEncoder()

# Fit the label encoder on the column data

le.fit(df[c])

# Transform the column to numeric

df[c] = le.transform(df[c])

# Save the label encoder to the label_encoder dictionary, indexed by the column name

label_encoder[c] = le

df.head()

| customerID | gender | SeniorCitizen | Partner | Dependents | tenure | PhoneService | MultipleLines | InternetService | OnlineSecurity | ... | DeviceProtection | TechSupport | StreamingTV | StreamingMovies | Contract | PaperlessBilling | PaymentMethod | MonthlyCharges | TotalCharges | Churn | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 7590-VHVEG | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No | ... | No | No | No | No | 0 | Yes | 2 | 29.85 | 29.85 | 0 |

| 1 | 5575-GNVDE | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Yes | ... | Yes | No | No | No | 1 | No | 3 | 56.95 | 1889.50 | 0 |

| 2 | 3668-QPYBK | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Yes | ... | No | No | No | No | 0 | Yes | 3 | 53.85 | 108.15 | 1 |

| 3 | 7795-CFOCW | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Yes | ... | Yes | Yes | No | No | 1 | No | 0 | 42.30 | 1840.75 | 0 |

| 4 | 9237-HQITU | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | No | ... | No | No | No | No | 0 | Yes | 2 | 70.70 | 151.65 | 1 |

5 rows × 21 columns

To make things easier, let’s just grab a few columns to work with.

sub_df = df[['gender', 'SeniorCitizen', 'tenure', 'MultipleLines', 'MonthlyCharges', 'TotalCharges'] + cat_cols]

sub_df.head()

| gender | SeniorCitizen | tenure | MultipleLines | MonthlyCharges | TotalCharges | Partner | Dependents | PhoneService | InternetService | Contract | PaymentMethod | Churn | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 29.85 | 29.85 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 34 | 1 | 56.95 | 1889.50 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 53.85 | 108.15 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | 45 | 0 | 42.30 | 1840.75 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 70.70 | 151.65 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

sub_df.dtypes

gender int64

SeniorCitizen int64

tenure int64

MultipleLines int64

MonthlyCharges float64

TotalCharges float64

Partner int64

Dependents int64

PhoneService int64

InternetService int64

Contract int64

PaymentMethod int64

Churn int64

dtype: object

Can we use logistic regression now? ¶

We said at the top of this notebook that logistic regression only works with continuous data, not categorical. But you may be wondering, why not just use logistic regression now that all columns are numbers? They may not be continuous, but they’re still numbers. In fact, you can use logistic regression (in that the commands will work). Let’s try before moving on.

# Create the logistic regression object

clf = LogisticRegression()

# Train-test split the data

train_df, test_df = train_test_split(sub_df, test_size=0.3)

# Split up the columns into the input and output

X_cols = ['gender', 'SeniorCitizen', 'tenure', 'MultipleLines', 'MonthlyCharges', 'TotalCharges', 'Partner', 'Dependents', 'PhoneService', 'InternetService', 'Contract', 'PaymentMethod']

y_col = 'Churn'

# Create the training set

X_train = train_df[X_cols]

y_train = train_df[y_col]

# Create the testing set

X_test = test_df[X_cols]

y_test = test_df[y_col]

# Fit the model on the training data

clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Make predictions on the testing data

y_pred = clf.predict(X_test)

# Classification report to see how we did

print(classification_report(y_test, y_pred))

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.84 0.88 0.86 1559

1 0.62 0.54 0.57 551

accuracy 0.79 2110

macro avg 0.73 0.71 0.72 2110

weighted avg 0.78 0.79 0.79 2110

This seems reasonable. We are getting decent precision, recall and f1-score. We will keep these results as a baseline. Once we learn about more models in this notebook, we will see how the results compare.

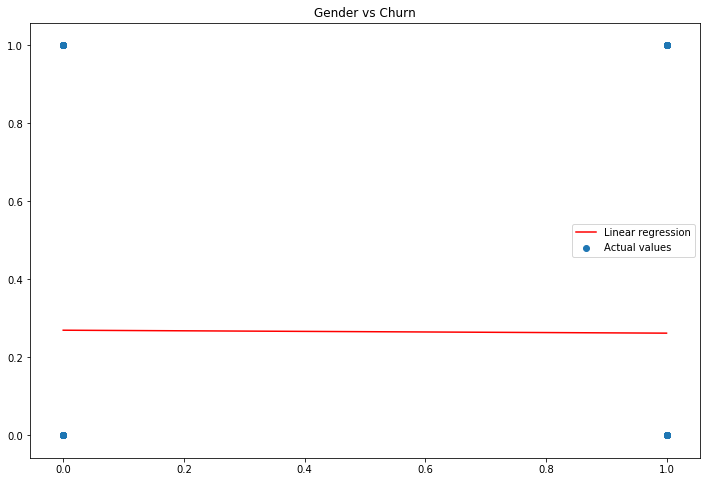

Regardless, it’s worth pointing out that this is a bad model, even if the results look good. The reason is that logistic regression is really just linear regression in disguise. Recall from last week that logistic regression fits a line \(f(x)\) so that \(\sigma\Bigl(f(x)\Bigr)\) (\(\sigma\) is the sigmoid function) best predicts the probabilities of each class. The line is fit based on the data. However, if we make a scatterplot of, say, gender versus Churn we get the following:

sub_df.plot(x='gender', y='Churn', kind='scatter', figsize=(12, 8))

<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot at 0x120c9aa60>

How could we possibly fit a line to this? Even though the axes makes it look like the data is continuous, each one only takes values 0 or 1. So, while sklearn will gladly fit a line to this (shown below), it is garbage. This illustrates why you need to understand what a model is doing, as opposed to simply memorizing commands.

# Line of best fit for gender vs churn

lr = LinearRegression()

X = sub_df[['gender']]

y = sub_df['Churn']

lr.fit(X, y)

# Plot the scatterplot and the line

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

plt.scatter(X, y, label='Actual values')

X_for_line = np.linspace(0, 1, 2).reshape(-1, 1)

plt.plot(X_for_line, lr.predict(X_for_line), label='Linear regression', color='red')

plt.legend()

plt.title('Gender vs Churn');

What an amazing line of best fit! So in summary, don’t do this. Anyone who knows what they are doing would look at this code and say “this person has no idea how logistic regression works.”

Supervised vs unsupervised models ¶

Up until this point all models we have learned are what are called “supervised models.” By a supervised model we mean a model trained by telling it what the ground truth is (the correct labels), and having the model learn to predict these values. You may think that this is the only way we possibly could train a model. After all, how could a model possibly learn to make correct predictions if it doesn’t know what the correct answer is! However, consider the following situation: You move to a new country where you don’t speak the language. You want to buy a train ticket to go visit another city, however you don’t know how much the ticket will cost. Moreover, since you don’t speak the language you can’t ask anyone how much it costs. However, as you’re waiting in line you watch the other people buying tickets. You notice the people in the same line as you all seem to pay around \\(20. Therefore, you decide that you'll also just hand the cashier \\\)20, and hopefully that will be the correct amount of money. You don’t know the answer for how much the ticket will cost. However, by observing people around you you are able to make a prediction. This is exactly how many unsupervised models work. By an unsupervised model we mean a model that learns its form by comparing its predictions to the ground truth.

Nearest neighbors ¶

Nearest neighbors is one of the most common unsupervised models. It works by looking at the points closest to it (hence the name “nearest neighbors”), and predicts the same label as those points do. So while nearest neighbors uses the ground truth so that it can see what its neighbors are predicting, it does not adjust its predictions based on whether or not it got the correct answer. Let’s jump right into an example.

At this point you should be starting to get more comfortable with how sklearn models work. Therefore, we will skip the details of the code below, but ask you to fill in the details yourself using the sklearn documentation.

nn_clf = KNeighborsClassifier()

nn_clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

KNeighborsClassifier(algorithm='auto', leaf_size=30, metric='minkowski',

metric_params=None, n_jobs=None, n_neighbors=5, p=2,

weights='uniform')

nn_clf.predict(X_test)

array([0, 1, 0, ..., 0, 1, 0])

nn_clf.predict_proba(X_test)

array([[0.8, 0.2],

[0. , 1. ],

[0.8, 0.2],

...,

[1. , 0. ],

[0.4, 0.6],

[0.6, 0.4]])

As you can see, the nearest neighbors model is predicting which class each sample should belong to, along with the probability (if you use .predict_proba()). This should look just like the results of logistic regression:

# Logistic regression predictions

clf.predict(X_test)

array([0, 1, 0, ..., 0, 0, 1])

# Logistic regression predicted probabilities

clf.predict_proba(X_test)

array([[0.62635386, 0.37364614],

[0.32739281, 0.67260719],

[0.55533517, 0.44466483],

...,

[0.98057425, 0.01942575],

[0.52777754, 0.47222246],

[0.45268345, 0.54731655]])

Before we do any further, let’s look at the classification report to see how this new model did.

y_pred_nn = nn_clf.predict(X_test)

print(classification_report(y_test, y_pred_nn))

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.83 0.88 0.86 1559

1 0.59 0.50 0.54 551

accuracy 0.78 2110

macro avg 0.71 0.69 0.70 2110

weighted avg 0.77 0.78 0.77 2110

If you look above at the classification report for logistic regression you will see that this nearest neighbors model actually achieves similar results. The f1-scores are very similar, along with precision and recall. However, as we discussed above, logistic regression would be a poor choice of a model, even if the results looked better. Remember that what this nearest neighbors model is doing is looking at similar ISP customers and making predictions based on those. Therefore, we are using a model that learns from already existing customers. This is totally logical.

While the initial results from our nearest neighbors model is decent, there is actually more we can do to improve it. For one thing, nearest neighbors makes its predictions by looking at the number of neighbors. How many neighbors is it looking at? If you look at the sklearn documentation you will see that by default it uses five neighbors. Let’s try some different values and see how the results compare.

# Build models with different number of neighbors used for prediction

for n_neighbors in [1, 5, 10, 15]:

# Build the classifier

nn_clf = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=n_neighbors)

# Train it

nn_clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Make predictions on the test set

y_pred_nn = nn_clf.predict(X_test)

# Print the classification report

print(f'{n_neighbors} neighbors')

print(classification_report(y_test, y_pred_nn))

print('='*40)

1 neighbors

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.82 0.80 0.81 1559

1 0.46 0.49 0.48 551

accuracy 0.72 2110

macro avg 0.64 0.64 0.64 2110

weighted avg 0.72 0.72 0.72 2110

========================================

5 neighbors

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.83 0.88 0.86 1559

1 0.59 0.50 0.54 551

accuracy 0.78 2110

macro avg 0.71 0.69 0.70 2110

weighted avg 0.77 0.78 0.77 2110

========================================

10 neighbors

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.81 0.93 0.86 1559

1 0.65 0.39 0.49 551

accuracy 0.79 2110

macro avg 0.73 0.66 0.68 2110

weighted avg 0.77 0.79 0.77 2110

========================================

15 neighbors

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.82 0.92 0.86 1559

1 0.64 0.43 0.52 551

accuracy 0.79 2110

macro avg 0.73 0.67 0.69 2110

weighted avg 0.77 0.79 0.77 2110

========================================

So it seems like the f1-score is best for both classes around 5 neighbors.

One question you should be asking yourself is, “how is the model measuring ‘nearest’?” In particular, if you think back to the original data, we had values like “Yes”, “No”, “Multiple phone lines”, etc. So which is closer, “Yes” and “No”, or “Yes” and “Multiple phone lines”? It doesn’t really make sense to say one is closer than the other, they’re just words. By default, nearest neighbors is using the usual Euclidean distance function. So it says that 0 is closer 1 than it is to 2. This is bad for our data, since 0, 1 and 2 are just numbers randomly assigned to each value. If we changed what values we assigned to them we would get different results. Luckily for us, sklearn allows you to pick different distance functions. We are in the situation of having integer values, so we should pick a function from the “Metrics intended for integer-valued vector spaces” list. Hamming distance is simply the number of neighbors with different values (so, for instance, number of neighbors who don’t have “multiple phone lines”, divided by the total number of neighbors). Therefore, a point is “close” if this distance is small, and thus if the neighbor has the same values. Let’s use that distance function by specifying metric='hamming'.

# Build models with different number of neighbors used for prediction

for n_neighbors in [1, 5, 10, 15]:

# Build the classifier

nn_clf = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=n_neighbors, metric='hamming')

# Train it

nn_clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Make predictions on the test set

y_pred_nn = nn_clf.predict(X_test)

# Print the classification report

print(f'{n_neighbors} neighbors')

print(classification_report(y_test, y_pred_nn))

print('='*40)

1 neighbors

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.83 0.76 0.80 1559

1 0.46 0.57 0.51 551

accuracy 0.71 2110

macro avg 0.65 0.67 0.65 2110

weighted avg 0.74 0.71 0.72 2110

========================================

5 neighbors

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.85 0.77 0.81 1559

1 0.49 0.62 0.54 551

accuracy 0.73 2110

macro avg 0.67 0.69 0.68 2110

weighted avg 0.75 0.73 0.74 2110

========================================

10 neighbors

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.84 0.81 0.83 1559

1 0.52 0.57 0.54 551

accuracy 0.75 2110

macro avg 0.68 0.69 0.69 2110

weighted avg 0.76 0.75 0.75 2110

========================================

15 neighbors

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.86 0.77 0.81 1559

1 0.50 0.65 0.56 551

accuracy 0.74 2110

macro avg 0.68 0.71 0.69 2110

weighted avg 0.77 0.74 0.75 2110

========================================

While the f1-scores aren’t drastically different, we can see that the precision and recall values for each class are often closer together. Therefore, the results our model makes are more reliable, since we don’t have to say “if it predicts the customer will churn then I’m highly confident in the result, but if it predicts they won’t churn then it’s probably wrong.” Again, machine learning is not just about building models that return good metrics. It’s about building models for which you can defend their predictions. If an internet company is spending tens of millions of dollars based on your predictions, you need to be able to back up your model. Simply saying “it returned a high score” is not good enough.

Visualizing predictions using PCA ¶

Besides just tables of numbers, it would be nice to see what our model is predicting. The problem is that we have twelve input columns and one output column, so we would have to “see” 13 dimensional space. This is why we have to rely so much on metrics to help us “see” how our model is doing. However, we do have a tool at our disposal to help us. Principal component analysis (or PCA for short) is a mathematical technique to take a high dimensional vector space, and transform it into a lower dimensional vector space, while preserving the distance between points as much as possible. It’s beyond the scope of this course to go into the details of PCA, but here are several resources: 1, 2, 3. The short version is that PCA does the best job it can (in a strict mathematical sense) to take data in high dimensions and represent it in lower dimensions in a way that is “as close as possible” to the original data. Sklearn makes PCA very easy. Simply specify how many dimensions you want to reduce it to (referred to as the number of “components”) and .fit() it to your data, just like you did for your models.

# Use one of the better models

nn_clf = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=10, metric='hamming')

nn_clf.fit(X_train, y_train)

KNeighborsClassifier(algorithm='auto', leaf_size=30, metric='hamming',

metric_params=None, n_jobs=None, n_neighbors=10, p=2,

weights='uniform')

pca = PCA(n_components=2)

pca.fit(df[X_cols])

PCA(copy=True, iterated_power='auto', n_components=2, random_state=None,

svd_solver='auto', tol=0.0, whiten=False)

In order to see the data “transformed” into lower dimensions, use the .transform() method.

X_train_pca = pca.transform(X_train)

X_train_pca

array([[-2149.18993938, 38.88171609],

[-2264.34862277, -18.18256247],

[ 1283.41925878, 3.30003747],

...,

[-2164.00336359, 11.5014036 ],

[-2208.37301471, 31.39090074],

[-1357.21923612, -7.58733048]])

print(f'Data shape: {X_train.shape} (original) --> {X_train_pca.shape}')

Data shape: (4922, 12) (original) --> (4922, 2)

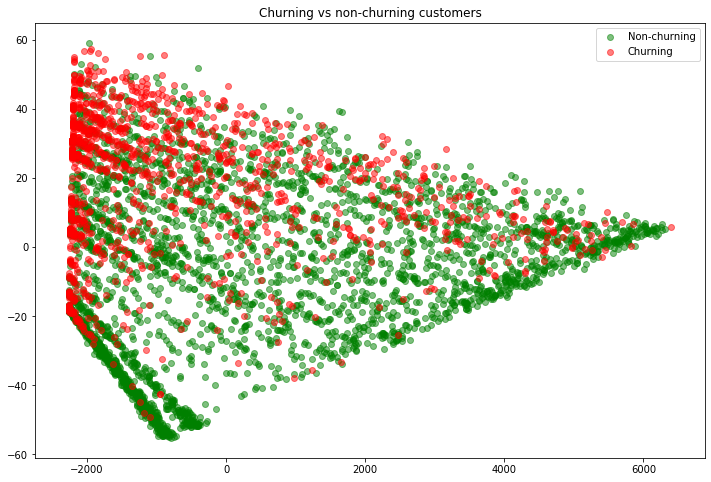

So we can see that the data went from having 12 columns (dimensions) down to just 2. In order to plot this, we’ll split up the data into churning and non-churning customers. We’ll print all the non-churning customers as green, and the churning customers as red.

def split_churn(df):

nonchurn_df = df[df['Churn'] == 0]

churn_df = df[df['Churn'] == 1]

X_nonchurn = nonchurn_df[X_cols]

y_nonchurn = nonchurn_df[y_col]

X_churn = churn_df[X_cols]

y_churn = churn_df[y_col]

return X_nonchurn, y_nonchurn, X_churn, y_churn

X_train_nonchurn, y_train_nonchurn, X_train_churn, y_train_churn = split_churn(train_df)

X_test_nonchurn, y_test_nonchurn, X_test_churn, y_test_churn = split_churn(test_df)

First let’s just PCA the X values for just the training data. We’ll peek at the data to see what it looks like, then plot it.

X_train_pca_nonchurn = pca.transform(X_train_nonchurn)

X_train_pca_churn = pca.transform(X_train_churn)

X_train_pca_nonchurn

array([[-2149.18993938, 38.88171609],

[ 1283.41925878, 3.30003747],

[-1593.80623066, -34.09533561],

...,

[ 775.06532704, -3.0332664 ],

[-2164.00336359, 11.5014036 ],

[-1357.21923612, -7.58733048]])

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

# Get all rows, but just the first/second column

plt.scatter(x=X_train_pca_nonchurn[:, 0], y=X_train_pca_nonchurn[:, 1], label='Non-churning', color='green', alpha=0.5)

plt.scatter(x=X_train_pca_churn[:, 0], y=X_train_pca_churn[:, 1], label='Churning', color='red', alpha=0.5)

plt.legend()

plt.title('Churning vs non-churning customers');

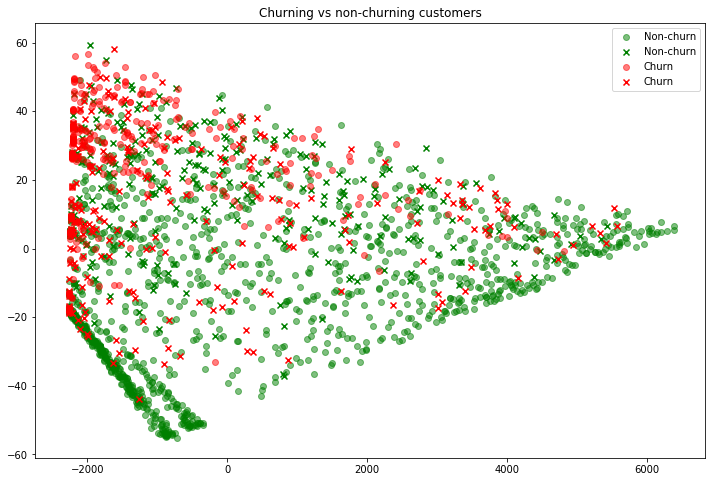

So you can see that the non-churning and churning customers each (somewhat) have their own “grouping”. This is good, because our nearest neighbors model will decide where a new (test) customer should fit (churn vs non-churn) based on its neighbors. It looks like this approach makes sense. Let’s now do the same for the test set. However, to get a better feel for how the model is doing, any points that were misclassified (so customers where our model said they would churn but in actuality they didn’t, or vice-versa) we will mark with an “x”. This is more advanced code and plotting, but I encourage you to try your best to understand it.

# Grab the churning and non-churning customers

X_test_nonchurn, y_test_nonchurn, X_test_churn, y_test_churn = split_churn(test_df)

# Use our nearest neighbors model to predict whether or not each customer in the test set will churn

y_pred_nonchurn = nn_clf.predict(X_test_nonchurn)

y_pred_churn = nn_clf.predict(X_test_churn)

# Find which predictions were correct

correct_nonchurn_preds = y_pred_nonchurn == y_test_nonchurn

correct_churn_preds = y_pred_churn == y_test_churn

# Grab the nonchurn customers from X_test

X_test_nonchurn_correct = X_test_nonchurn.loc[correct_nonchurn_preds]

# Also grab the incorrect predictions. Here "~" means "not", and it inverts True and False. So ~True == False

X_test_nonchurn_wrong = X_test_nonchurn.loc[~correct_nonchurn_preds]

# Grab the churn customers from X_test

X_test_churn_correct = X_test_churn.loc[correct_churn_preds]

X_test_churn_wrong = X_test_churn.loc[~correct_churn_preds]

# Next we'll PCA all four groups

X_test_nonchurn_correct_pca = pca.transform(X_test_nonchurn_correct)

X_test_nonchurn_wrong_pca = pca.transform(X_test_nonchurn_wrong)

X_test_churn_correct_pca = pca.transform(X_test_churn_correct)

X_test_churn_wrong_pca = pca.transform(X_test_churn_wrong)

# Finally, we'll plot all four groups, making those with an incorrect prediction an "x"

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(12, 8))

plt.scatter(x=X_test_nonchurn_correct_pca[:, 0], y=X_test_nonchurn_correct_pca[:, 1], label='Non-churn', color='green', alpha=0.5)

plt.scatter(x=X_test_nonchurn_wrong_pca[:, 0], y=X_test_nonchurn_wrong_pca[:, 1], label='Non-churn', color='green', alpha=1, marker='x')

plt.scatter(x=X_test_churn_correct_pca[:, 0], y=X_test_churn_correct_pca[:, 1], label='Churn', color='red', alpha=0.5)

plt.scatter(x=X_test_churn_wrong_pca[:, 0], y=X_test_churn_wrong_pca[:, 1], label='Churn', color='red', alpha=1, marker='x')

plt.legend()

plt.title('Churning vs non-churning customers');

Note that the color is the actual label. So “x“‘s are in the color that they should have been predicted, but were not. Thus we can see some interesting customers. For example, in the top-left is a customer who did not churn (green “x”). Our model predicted she would churn since she is “near” many other red points, however she did not. Similarly, those customers on the far-right who churned (red “x”) were predicted to churn, yet they didn’t. If you worked at this ISP it would be interesting to dive into these outliers and see if there are any obvious patterns about what makes them different. Perhaps they had a poor experience, or were given a special discount? At the same time, remember that the scatter plot above is trying to display 12 dimensional data in 2d, so any conclusions we make from this need to be taken with a grain of salt.

Exercises¶

We (somewhat randomly) picked some columns for

X_colsto train our model on. Are these the best columns to use? Try looking through the columns in the original data and seeing if you can come up with some better columns.Try nearest neighbors with different number of neighbors to see if you get better results.

Try some different distance metrics for nearest neighbors.

PCA down to three dimensions, then plot these in a three dimensional graph (Google it!)

Try all of this with new data!